Over a million ways and counting to remember a father

Dan Leksell reflects on the life and times of his father, Professor Lars Leksell, creator of Leksell Gamma Knife

By virtue of ongoing upgrades and improvements, Elekta’s Leksell Gamma Knife® has demonstrated remarkable staying power and clinical relevance. In 2018, Elekta celebrates the 50th anniversary of the start of the system’s use in the clinic. The building block for Gamma Knife was the stereotactic frame that Professor Lars Leksell developed in 1949 and which was integrated with a radiation unit to create the clinical system in 1968. In this Wavelength article, one of Prof. Leksell’s son, Dan Leksell, remembers some amusing and interesting anecdotes about collaborating with his father.

Life with Lars Leksell

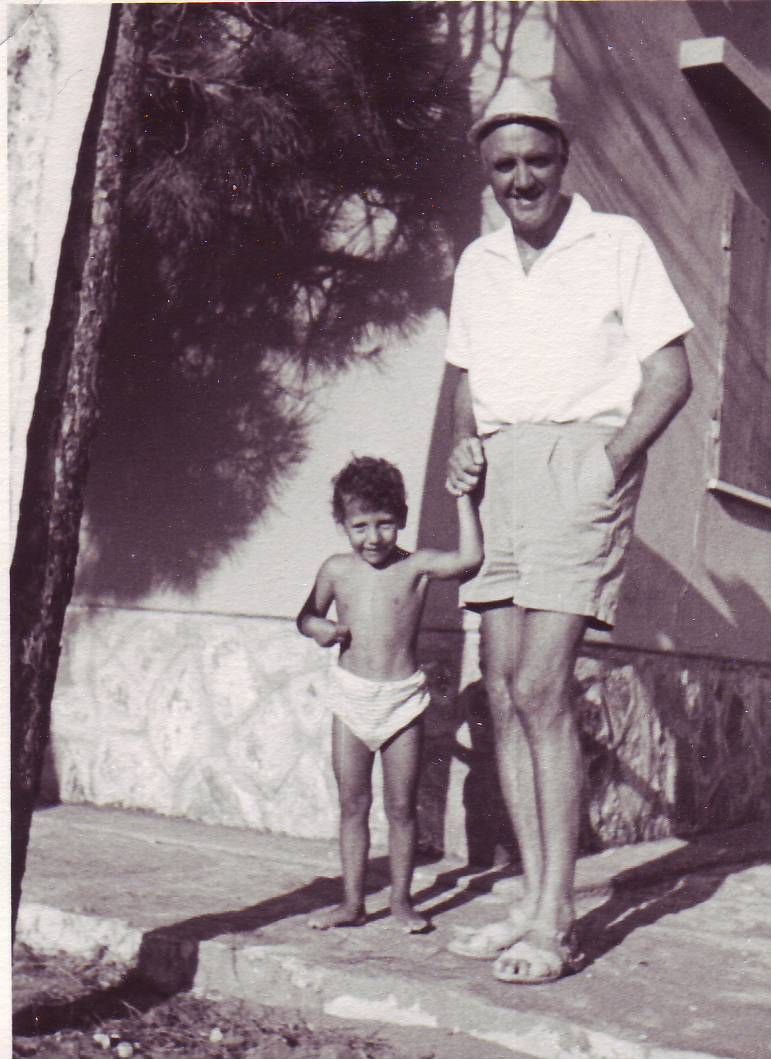

Until I was 15-years-old, when my mother died, life with my father was easy. Except for a few summer weekends in the countryside, we had very little interaction. However, one thing he managed to do during those early years was to infect me with his interest in stereotaxy, in the instrument, and, later on, in radiosurgery, among many other things. He often brought home the instrument in the evening to tinker with and make improvements.

Globetrotting on my father’s behalf

My father was frequently invited to give talks at meetings all over the world. I was fortunate in that he didn’t like traveling. He preferred to stay at the Karolinska Hospital and work with his younger colleagues, engineers and physicists. When he realized that I was going into medicine, he started to increasingly make use of his doctor-to-be son as a proxy to give talks. He usually approached me only one or two days before I had to leave – without having put together neither manuscript nor slides for his talk.

One particularly memorable meeting was in India in 1968. We had just started using the prototype Gamma Knife in Stockholm, when my father was invited by Professor Ramamurthi to speak. Picture this: I was an 18-year-old hippie nerd in my final year of school and talking to the Indian Neurosurgical Society about using Gamma Knife to treat brain tumors – without opening the skull. It’s important to note that was also before we had published even a single paper on the subject. And I wasn’t smart enough to be nervous during the 40-minute talk.

The reaction of the Society members was harsh and understandable, mostly to the effect of: “Who is this charlatan? Throw him out!” And that’s just what they did. The next thing I knew, I was standing alone outside, feeling sorry for myself. With nothing else to do, I ate from a huge outdoor buffet next to a sacred zebu cow that was thoroughly enjoying it with me.

The Italian scandal

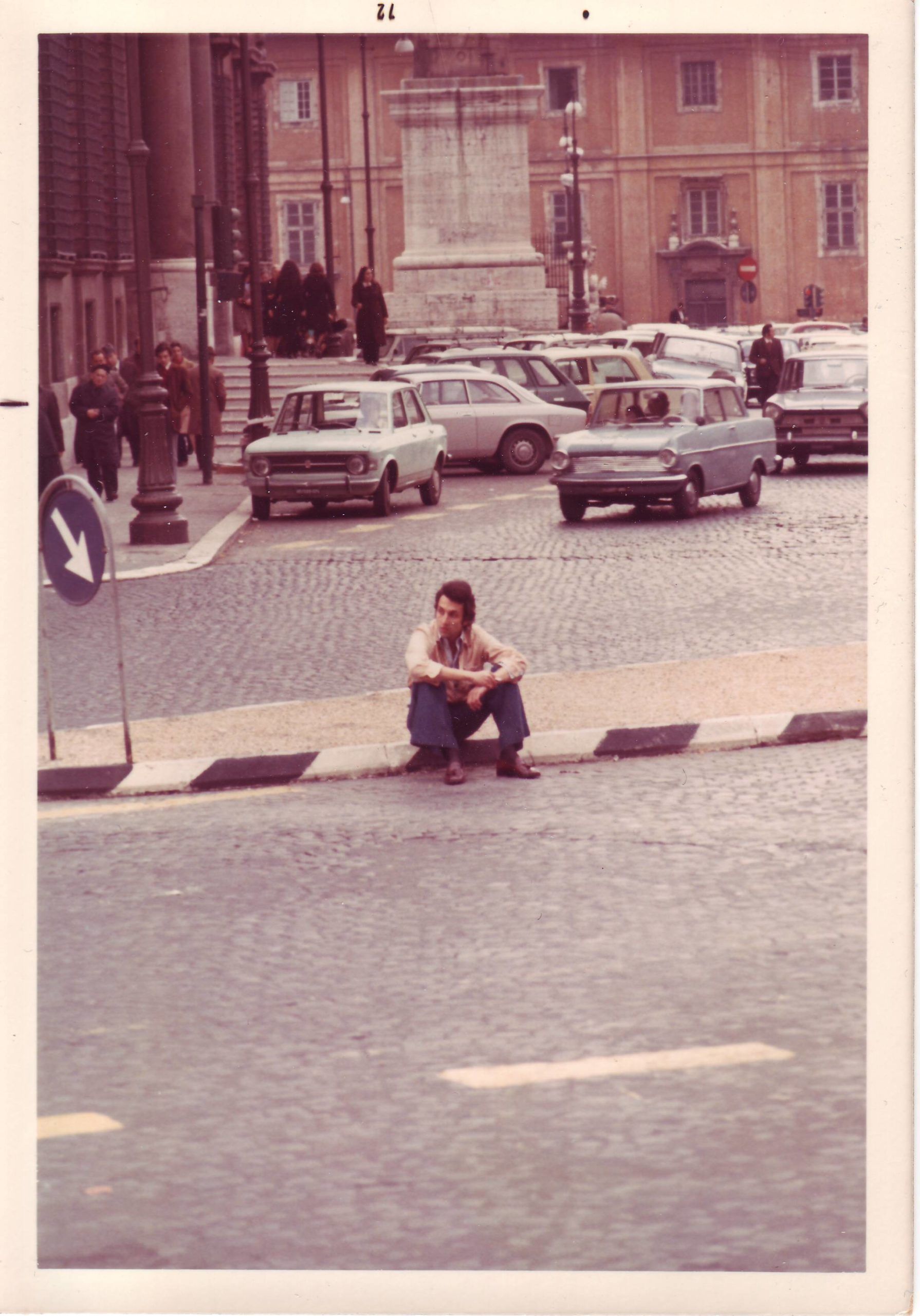

My father often evaluated patients in Italy, mostly patients with Parkinson’s disease, just as his predecessor, Herbert Olivecrona, had done before him. He selected patients who could be helped by a stereotactic thalamotomy and who would then travel to Stockholm for the procedure. It was usually a two-day affair, assessing about 25 cases per day. In 1971, just a couple of days before he was due to travel to Rome, he again claimed some kind of esoteric “affliction” and said that he needed my help. I was now in my third year at medical school, was done with my neurology exam and had sat with him through evaluations of many of these patients. So while I didn’t hesitate much, I certainly wasn’t certified to act as a doctor.

I was sitting with a patient on my first day in Rome when a nurse came in and announced that the police were outside, waiting to speak with me. A doctor at the clinic had gotten wind of my unauthorized presence. I said goodbye to the patient and jumped out of the window into the back garden of the clinic and took a taxi to the airport. I didn’t bother to check out of my hotel – I got out on first flight out of Rome.

When I landed in Stockholm I was surprised to see my father waiting for me at the gate. This was the first and only time ever that he met me at the airport. His conscience must have been darker than a Swedish night in the middle of winter. The next day the scandal was reported by all the major Italian newspapers: the medical-student son, impersonating Professor Lars Leksell, illegally seeing patients in a private clinic in Rome. The news reached a newspaper in the south of Sweden, but luckily I managed to stop further spread in the Swedish press. My medical career could have ended right there.

The year 1981 was the last time I was struck with my father’s penchant for “getting sick” 24 hours before he was due to travel. He was invited to give the Sir Hugh Cairns Memorial Lecture, one of the most prestigious neurosurgical honors in the U.K. By now I had long since developed a routine for handling these emergencies. I collected my slides, flew to Manchester, and at midnight drove over the mountains to Sheffield. The weather was terrible and halfway there my rental car went off the road. I bumped my head and lost consciousness. When I regained consciousness I was lucky to get a lift to Sheffield, I gave the talk and came home with his medal. Of course this habit of his caused a lot of grief and inconvenience. But in retrospect I have to say that, although I prefer to schedule my own trips and talks, traveling in my father’s stead afforded me many opportunities to meet a host of wonderful people in all corners of the world.

Times together

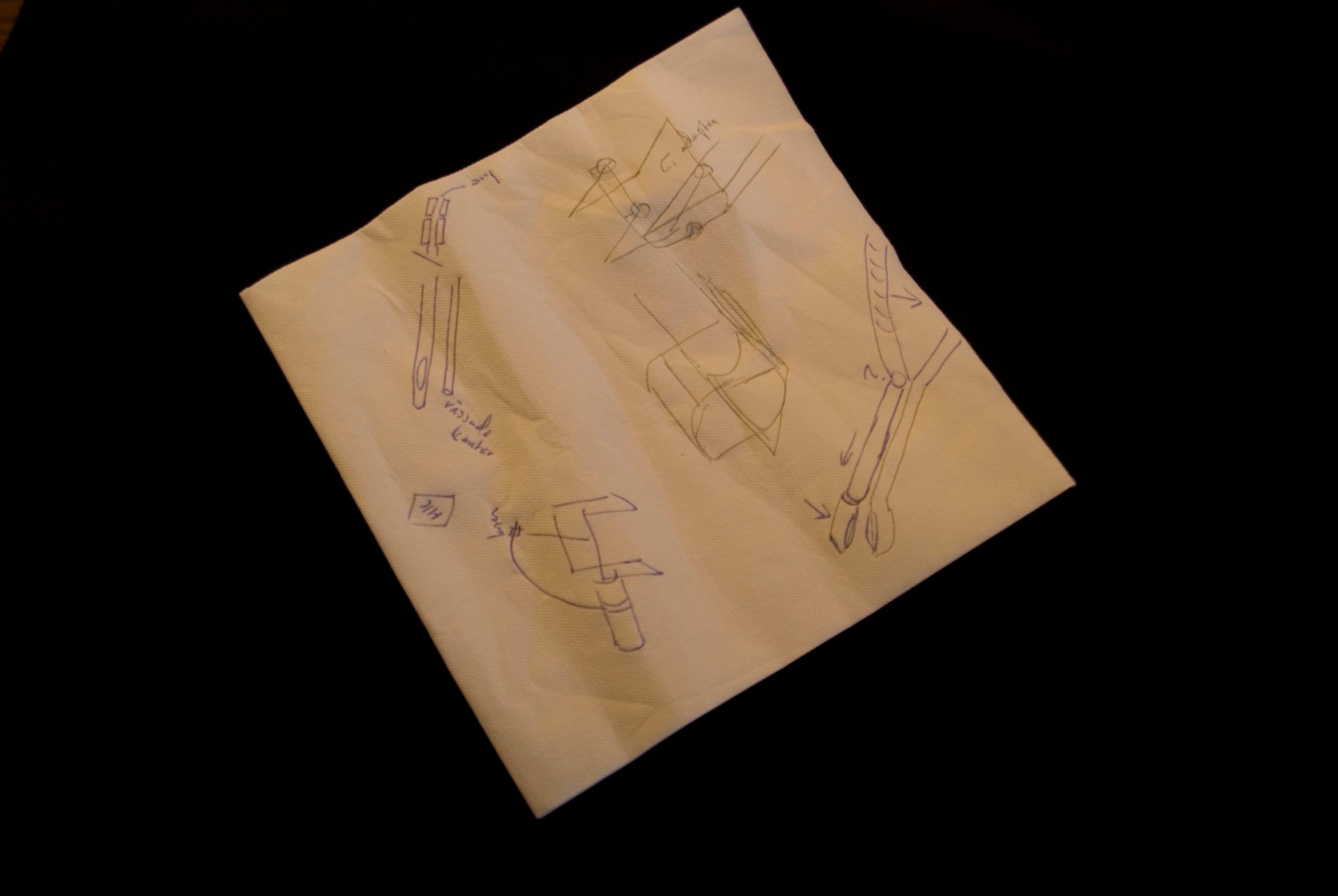

Between 1969 and the mid-1980s, my father and I developed a very close relationship based on mutual respect and an openness for sharing new ideas. At the time, my wife and I lived with our three children just a block from his apartment. As a result, he ate dinner with us at least three times a week. When this became too much for my wife, we solved this by simply going to the local restaurant together. During dinners we sketched our ideas on paper napkins and brainstormed around instrumentation and the potential clinical indications for radiosurgery.

Curiosity, passion, patience

My father had an innate curiosity in a wide variety of fields. When I worked on my thesis he would come to the lab to see any new findings, to listen and offer ideas. He had a good sense of aesthetics, which often was useful to me and which manifested itself in his instrument designs. He was an avid reader and often, somewhat jokingly, scorned me for being illiterate. He loved classical music and ballet. Anything involving technical matters, such as cars, boats and motorcycles interested him greatly. He loved his Daimler, but not enough to get very upset when I, at 16 and without a driver’s license, totaled the vehicle. He simply asked me to be a little more careful and to use my brain before I let my teenage impulses take over.

Last days, fond memories

In January 1986, my father was spending a few weeks at a ski resort in Switzerland. He was writing a new book when his dictating machine broke. I was on call and in the OR with an emergency, when he called me at five in the morning asking me to buy a new Dictaphone® and send it to him in Switzerland.

Stressed and tired, I didn’t control my words and gave him a rude tirade about how improper it was of him to call about such a trivial matter at such an inopportune hour. Later that day I got the machine and sent it to him. Many of us likely regret something we did to our parents that weighs heavily on our conscience. This episode became mine. That same day he had a cardiac arrest and died. To this day, I wish I had been more thoughtful when I took his call in that operating room.

On the day of his funeral the church was completely filled and the mood was somber; everyone was sad and quiet. As people filed past his casket, there were two who very loudly and uncontrollably wept – they were the two wonderful servers who had fed us during all of our dinners at the local restaurant.

So, how was life with Lars Leksell? Sure, it was demanding when I had to do things for which I was neither prepared nor competent. It was hard to strike a balance between being less than competent and not losing face.

On the other hand, there was tremendous stimulation and many sweet memories, from serious and less serious times spent together.

Today, after 32 years, I still miss him very much.