Addressing skin tone inequalities in radiotherapy

UK radiographer spearheads effort to focus on health equality for people of color

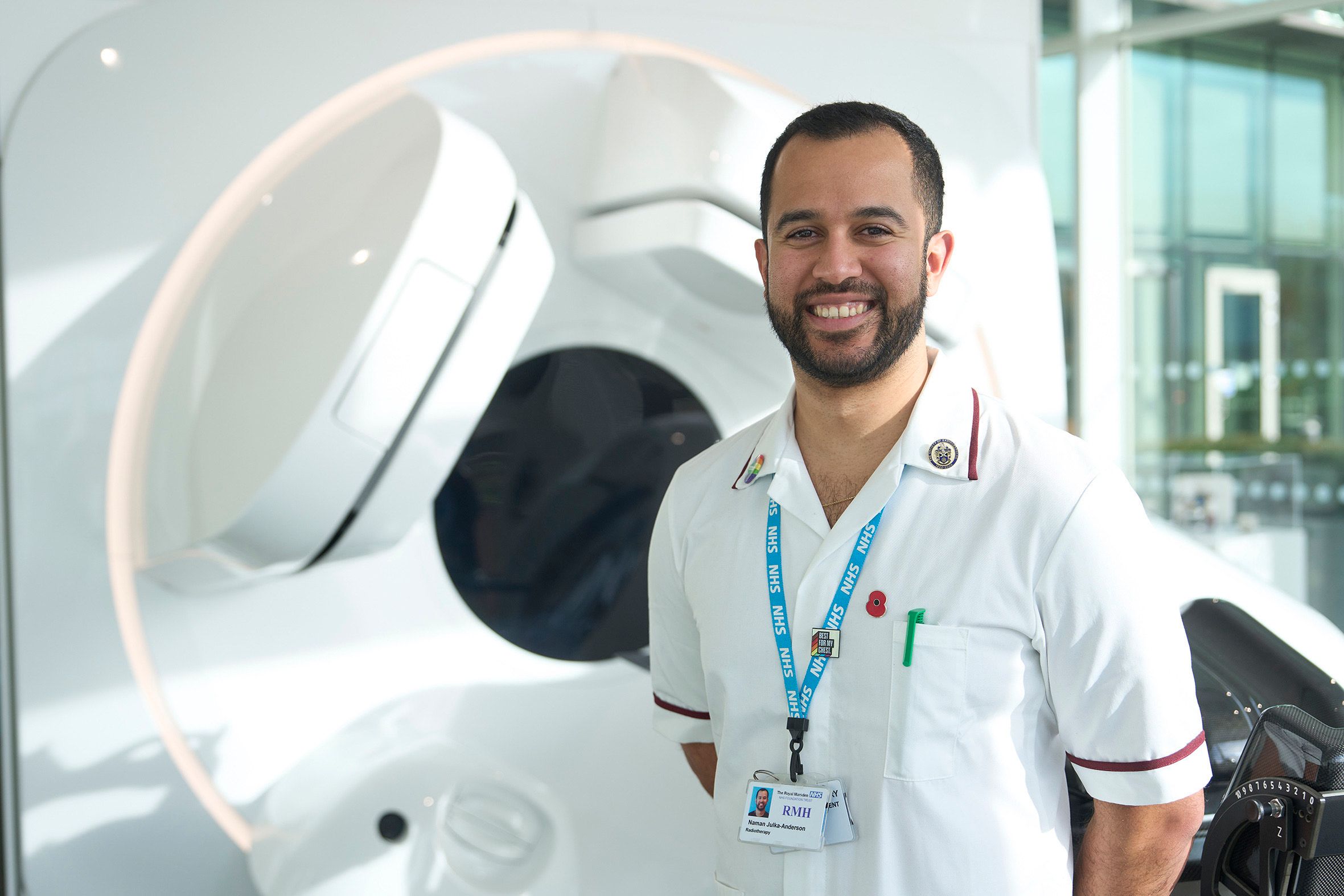

In 2021, radiographer Naman Julka-Anderson had an epiphany when he consulted with a Black male head-and-neck cancer patient who had received 22 fractions (48 Gy total dose) of radiation therapy. The physicians had instructed the patient to watch for “redness” within the treatment area, an acute side effect highlighted on the consent form. The patient described the reaction as feeling like their skin was “on fire.” Although their skin made a full recovery, the patient sought support through the local psych-oncology team, because throughout this ordeal they had felt ‘“helpless.”’1

“That’s the first time the importance of skin tone differences really hit me,” Naman remembers. “When I was working on my Master’s degree to qualify for a radiotherapy and oncology position, the impact of radiotherapy on a patient’s skin was always measured by ‘redness’ [i.e., erythema]. For this particular patient, I had alerted a colleague that the patient’s skin reaction was getting quite bad, but they told me: ‘You’re a junior radiographer. You don’t know what you’re talking about. Send the patient home.’”

An under-researched area

According to Naman, for as long as radiotherapy has been practiced, limited attention has been paid to how radiation side effects present on the skin of people of color (POC). As a result, radiation induced skin reactions (RISR) terminology, consent forms, education, and assessment tools (e.g., RTOG, CTAE, RISRAS) developed in the 1990’s have not changed at all and have been biased toward white skin as the “norm.” For example, as late as 2019, AI software used in American centers was “found to have been systematically discriminating against Black people…as the use of white skin tone patients is well documented as the primary group for algorithms in AI software and pulse oximetry.”2-6

Following that first head-and-neck cancer patient, Naman’s direct foray into RISR research was to reference a 2020 Society of Radiographers UK skin care guidance. He searched the document for “Black,” “Asian” and “person of color,” but couldn’t find these terms along with other similar guidance documents.

“There has been limited research on how RISR presents on different skin tones.”

“There has been limited research on how RISR presents on different skin tones,” he says. “Following this, Prof. Heidi Probst and Dr. Rachel Harris mentored me on the beginnings of my research journey as I navigated literature and my own experiences. Their previous work with the Society of Radiographers radiation dermatitis guidelines 2020 helped me direct my research!

Because of these prejudices and inequalities, Naman has made the assessment of RISR – and how to address care inequalities among these individuals – a major focus of his career over the last 18 months. During this time, in addition to giving over 55 talks and webinars on the subject, he also published an authoritative peer-reviewed paper1 in the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, which was awarded “Best Clinical Perspective” in 2023 by the journal.

Many radiographers lack confidence in assessing RISR

Working with Dr. Harris and Prof. Probst under the auspices of the Society of Radiographers, Julka-Anderson led a UK survey titled: “Understanding Therapeutic Radiographers’ Confidence in Assessing, Managing & Teaching Radiation Induced Skin Reactions (RISR)” which is currently under review.

Among the 400 respondents who completed the survey, 72 percent were confident when assessing white skin, but just 42 percent reported confidence in assessing brown or black skin.

Subsequently, Prof. Probst recommended that he give a talk at ESTRO 2022 in a well-attended meeting track covering health inequalities.

“I just very bluntly put it that we are doing things wrong and explained with some visuals of acne and psoriasis that showed the disparate presentations of these common skin problems between white and black skin – how we don’t see redness on the latter skin tones,” Naman says.

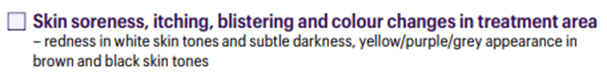

Advancing his mission after ESTRO 2022, Naman contacted the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR), which earlier in the year had released its radiotherapy consent forms, documents that still emphasized erythema as the RISR to watch for.

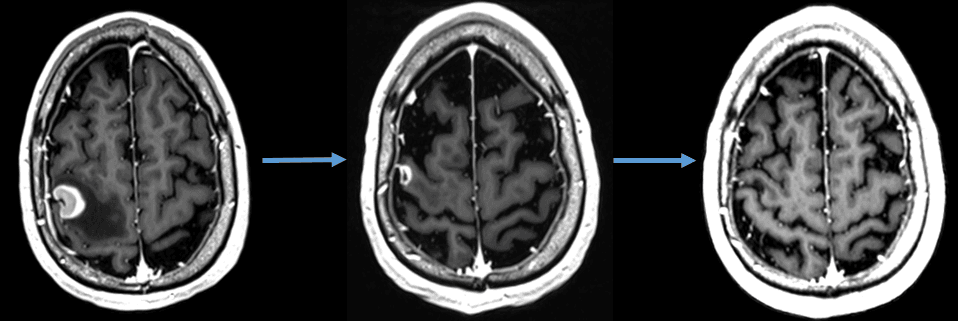

“I was able to work with the core team at RCR to suggest how to appropriately reword the consent forms to include RISR distinctions between patients with white, brown or black skin,” he says. “That was amazing and quite a big win that I’m quite proud of on behalf of people of color, we will now be consented for radiotherapy with the correct terminology.” (See Figure 1)

Other inequalities demonstrate lack of attention to POC

Healthcare inequalities aren’t confined to RISR assessments, according to Naman. Many healthcare systems don’t consider post-therapy accommodations, such as prostheses and wigs. For example, in 2021, when he was evaluating RISR in a Nigerian breast cancer patient who had undergone a unilateral mastectomy, he observed that her prosthetic breast was white.

“I asked her about it and she said they told her that skin tone was all they had,” he recalls. “We both sort of awkwardly laughed about it. That was something new to me – I wasn’t taught that at university. I had thought the NHS catered for everyone equally.”

In a similar instance, Naman saw a Black patient who had received chemotherapy and lost her hair, which was afro-styled and black.

“She was offered a wig of straight, blonde hair, because that was all they had,” he says.

The path forward for equality in radiotherapy

Some progress had been made in recognizing the needs of people of color as they navigate their cancer care journey, but the discipline is still on the starting block, according to Naman.

“My journal article1 will be published in 2024 [paper version], but we’re still miles away from giving people of color what they deserve, which is simply equitable treatment,” he says. “First, radiotherapy professionals just need to be honest about how things are. It’s not simply saying ‘We’ll improve our standards soon.’ Because that would still mean thousands of patients going through their treatment with incorrect clinical information.”

Continuing to remain unfamiliar with the needs of POC won’t do, Naman adds.

“As part of their patient care mission, radiation oncology professionals should really educate themselves on skin tone differences between white patients and persons of color…”

“As part of their patient care mission, radiation oncology professionals should really educate themselves on skin tone differences between white patients and persons of color and how that impacts their treatment,” he says. “They need to take an interest and learn.”

One way to learn is to check out Naman’s award-winning podcast that he co-hosts called Rad Chat, which is designed for cancer patients. Episode 7 is “Radiotherapy Skin Care.” Also, members of the Society of Radiographers can sign up to the RISR special interest group that Naman established.

In addition to Rad Chat, he cites other resources that provide a wealth of information on cancer treatment perspectives geared for POC. These include Black Women Rising, Sakoon Through Cancer (for South Asian patients), and, South Asian Super Novas and From Me to You.

References

- Julka-Anderson N. Structural racism in radiation induced skin reaction toxicity scoring. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2023 Oct 11:S1939-8654(23)01872-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2023.09.021. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37833117.

- Ledford H. Millions of black people affected by racial bias in health-care algorithms. Nature. 2019 Oct;574(7780):608-609. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-03228-6. PMID: 31664201.

- Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 17;383(25):2477-2478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2029240. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2021 Dec 23;385(26):2496. PMID: 33326721; PMCID: PMC7808260.

- Fawzy A, Wu TD, Wang K, Robinson ML, Farha J, Bradke A, Golden SH, Xu Y, Garibaldi BT. Racial and ethnic discrepancy in pulse oximetry and delayed identification of treatment eligibility among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2022 Jul 1;182(7):730-738. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.1906. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2022 Oct 1;182(10):1108. PMID: 35639368; PMCID: PMC9257583.

- Noor P. Can we trust AI not to further embed racial bias and prejudice? BMJ. 2020 Feb 12;368:m363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m363. PMID: 32051165.

- Powell RA, Njoku C, Elangovan R, et al. Tackling racism in UK health research. BMJ. 2022;376:3065574.

LARNPS240129