The Early Years

1972 - 1986

Reading time: 10 minutes

Neurosurgeon Lars Leksell invents Leksell Gamma Knife to treat brain cancer—without an open surgical procedure! Now, how will that impact traditional radiotherapy? Sons Larry and Danny help turn it all into a proper company.

Elekta was founded in 1972—but the story begins much earlier.

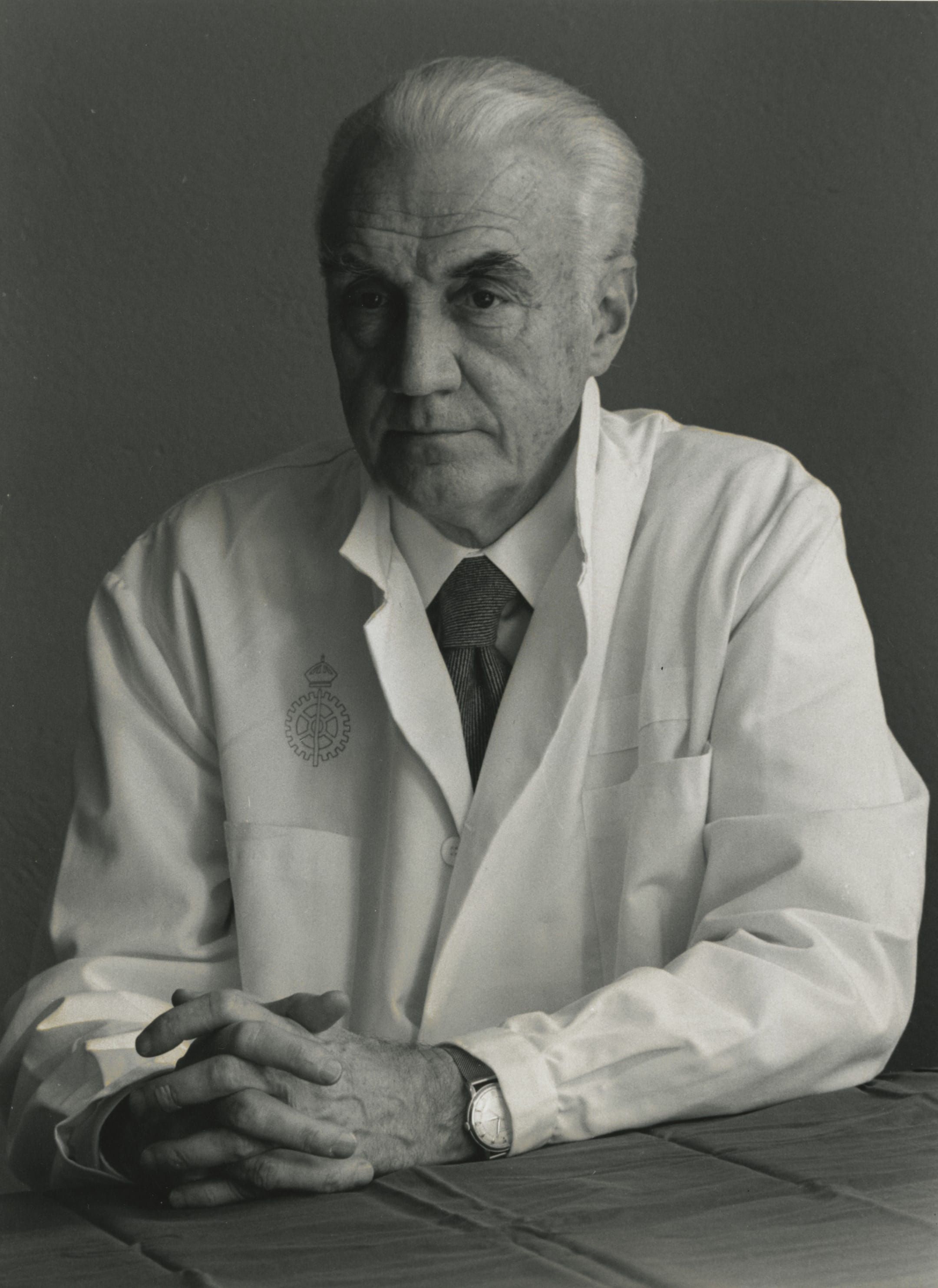

The background, creation and development of Elekta as a company is tightly connected to the vision of bloodless brain surgery and non-invasive cancer treatment. With the development of radiophysics during the first half of the 1900s, this vision moved from a dream to a research field of great potential. Swedish neurosurgeon Lars Leksell (1907–1986) started experiments shortly after World War II that eventually would result in the innovations that Elekta much later set out to commercialize. To begin with, however, that story had very little, if any, connection to the company’s creation.

The emergence of modern brain surgery

Neurosurgery emerged as a modern clinical practice and profession only during the late 1800s. The world’s first neurosurgeon position was established at Queen Square, London, for Victor Horsley, in 1886. Horsley was the first to perform successful operations on brain and spine tumors and was followed by the American, Harvey Cushing, at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, who refined Horsley’s techniques. Herbert Olivecrona (1891–1980) carried out Sweden’s first brain tumor operation in 1922 at the Serafimer Hospital in Stockholm. Olivecrona established the discipline in Sweden and became its first professor in 1935.

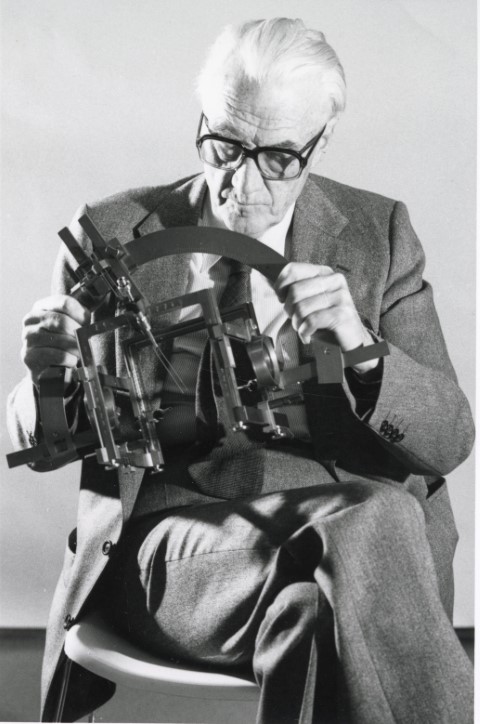

Lars Leksell was one of Olivecrona’s disciples and belonged to Sweden’s second generation of neurosurgeons. He combined skills as a surgeon with an ability to figure out solutions to the technical challenges of neurosurgery. One early example is the Leksell Rongeur (“Leksell-tång”), a flexible set of neurosurgical pliers, based on Leksell’s experiences from removing shell splinters from injured spines during his service as a volunteer physician in Finland during the war. The Leksell Rongeur is a classical surgical instrument, still in worldwide use.

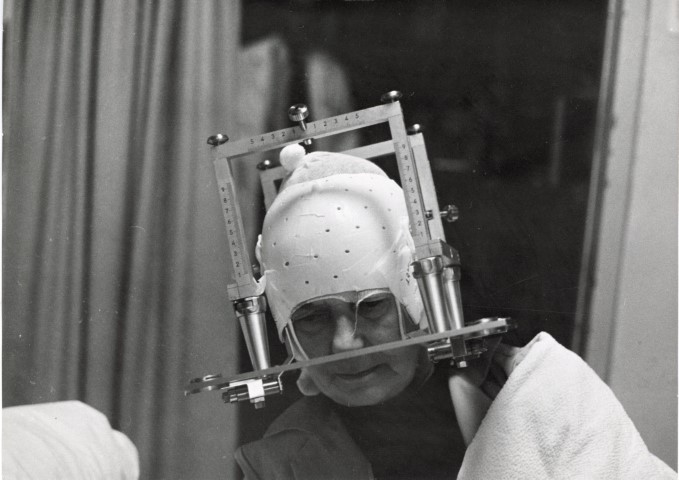

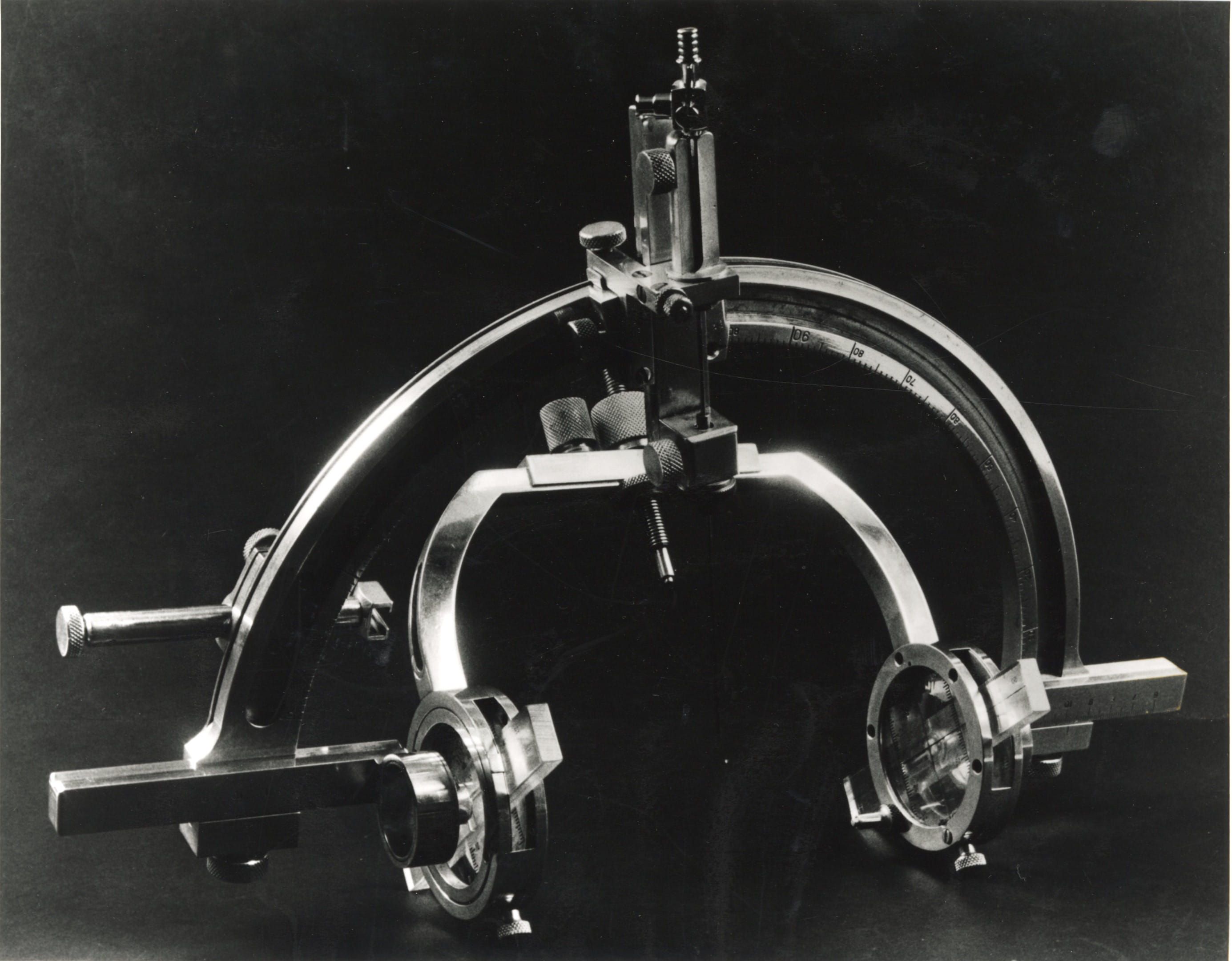

After receiving his doctoral degree in 1945, the University Hospital in Lund recruited Leksell to set up the first neurosurgical clinic in the country outside of Stockholm. In Lund, Leksell started work on a totally different kind of instrument, a three-dimensional head frame, or arc, with electrodes, using coordinates to locate small, injured targets inside the brain. This instrument, the Leksell Stereotactic System, was an improvement over previous stereotactic solutions by other researchers; it increased precision and minimized, if not eliminated, the surgical intervention to a small burr-hole, through which a probe could be inserted. The stereotactic instrument was first successfully tried intraoperatively in Lund in 1949. Already here, the innovation was driven by the ambition to minimize painful and perilous intervention for patients with serious diseases.

Combining radiophysics and surgery

Technical/medical inventions like the stereotactic instrument were significant and could be used in several forms of treatment, but the critical step in Leksell’s scientific development was when he started to combine this technology with radiophysical methods. Radiophysics had developed greatly during the interwar period and researchers considered new applications and uses, not least in the medical field.

The Gustaf Werner Institute for nuclear chemistry in Uppsala, headed by The Svedberg, Nobel laureate in chemistry, had, in the mid-1950s, acquired a synchrocyclotron, a powerful tool to produce proton radiation. This was used in the world’s first proton cancer treatment in 1957, on a cervical cancer patient in her 60s. Meanwhile, Leksell in Lund had started to explore what he named “stereotaxic radiosurgery,” using first x-ray, ionizing radiation and even ultrasound in combination with the stereotactic instrument. However, the effect of the radiation was too weak to have the anticipated results.

Proton radiation was much more powerful, and when Leksell teamed up with radiation biologist Börje Larsson at the Werner Institute, they could direct proton beams from the synchrocyclotron to exact targets inside the head, located by using the stereotactic instrument. Their first brain operation was carried out on site at the Werner Institute in late 1958. When the results were made public early the following year, newspapers celebrated the event as a medical–technical wonder. It was “the first brain operation with an ‘invisible knife’, where the surgeon’s instruments are replaced by a proton beam,” wrote daily Svensk Dagbladet in January 1959.

While the “Proton Knife” was a sensation, it was also contested. Several neurosurgeons stated that radiation hardly could substitute traditional surgery in any significant way. Even the main authority in the field, Herbert Olivecrona, expressed doubts that radiation would ever play a significant role in relation to “classical neurosurgery.” But Leksell and Larsson were convinced that they were heading in the right direction.

Bringing Gamma Knife to life

Lars Leksell, who in 1960 had moved to Stockholm to succeed Herbert Olivecrona as professor in neurosurgery at the Serafimer Hospital, continued to use the synchrocyclotron at the Werner Institute, mostly for patients dealing with Parkinson’s disease. The patients were prepared in Stockholm, where the rather large stereotactic frame was attached to their head. They were then driven an hour north to Uppsala, often in Leksell’s own car.

But the synchrocyclotron was really a general research facility for radiation physics and chemistry, used for several purposes apart from medical applications. Leksell and Börje Larsson therefore started to develop a tool that was specialized for clinical use and more suitable for their aims.

The premises at the Serafimer Hospital were too old and insufficient for what they needed. Instead, a new clinic with proper research facilities and a well-equipped mechanical workshop was established at the Karolinska Hospital in Solna, just north of Stockholm, in the early 1960s. Reluctant to leave the old premises, Leksell did appreciate the practical advantages of the new clinic. Also here was the cancer clinic Radiumhemmet, which performed conventional radiation treatment with linear accelerators. At Karolinska, much of Leksell’s and Larsson’s development work was put into practice.

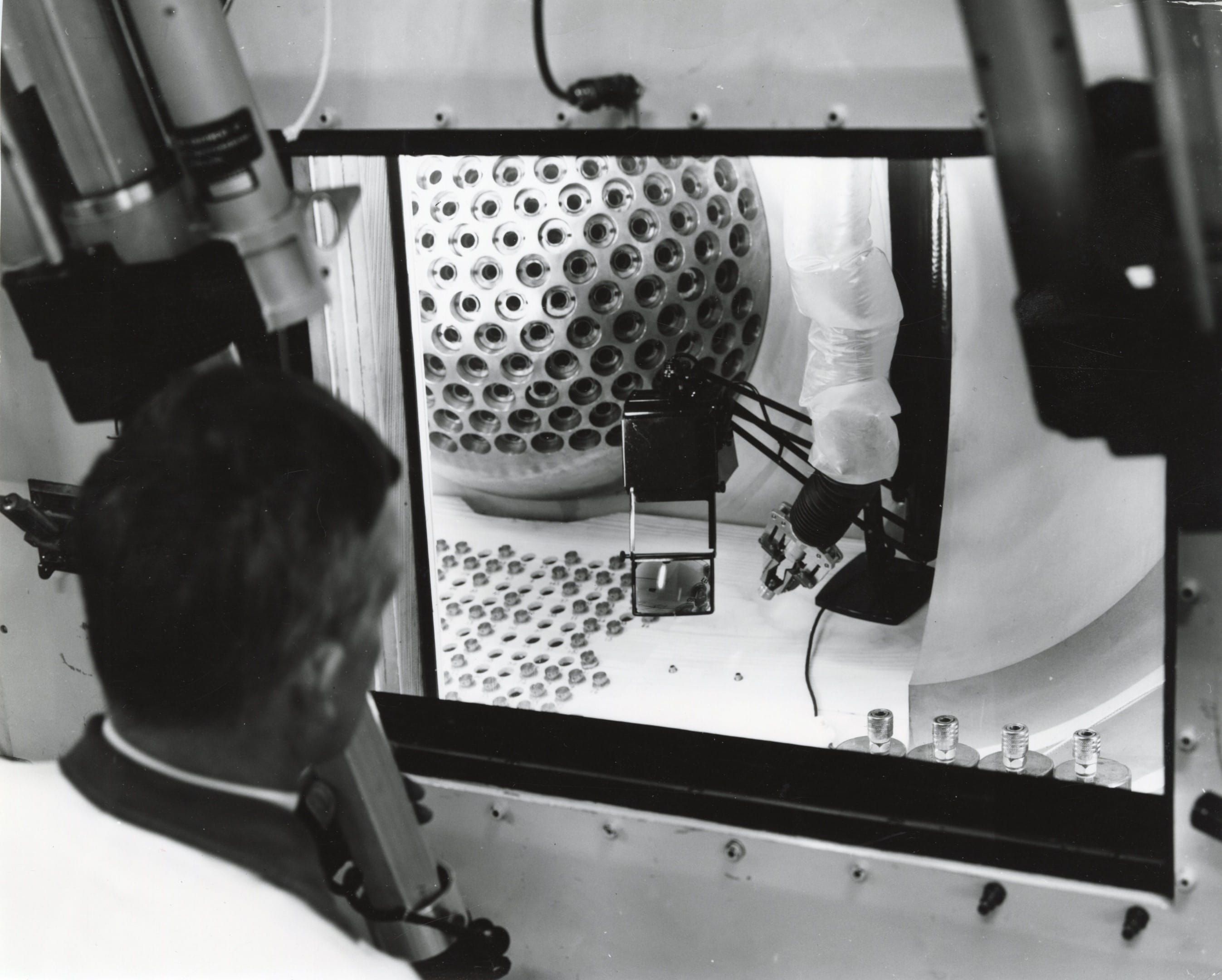

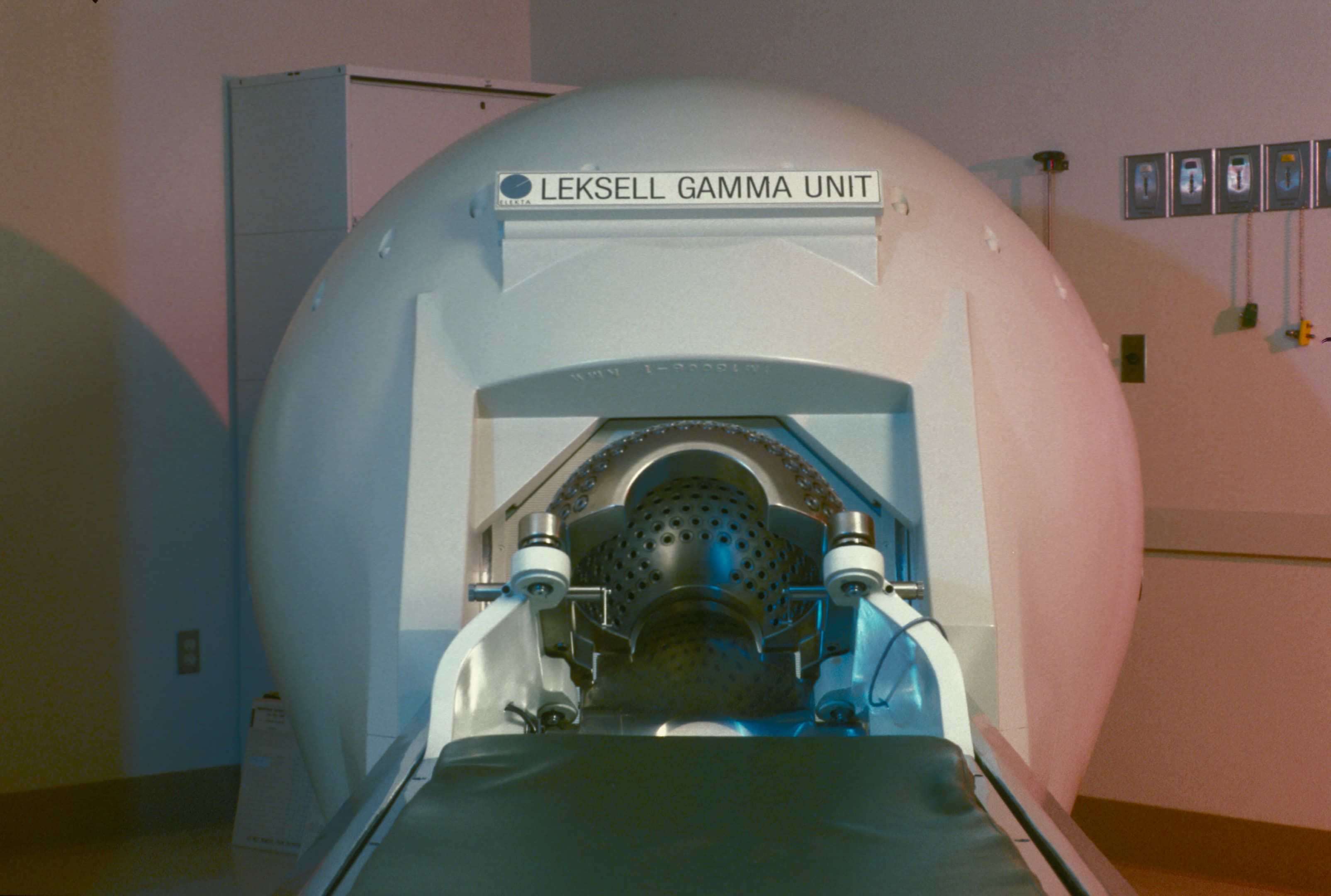

They eventually settled for gamma ray emissions of Cobalt-60 as a more efficient radiation source than the protons used in Uppsala. The stereotactic frame was complemented by a hemispheric helmet-like steel construction, to be placed around the patient’s head. This helmet was supplied with no less than 180 independent sources of radiation, evenly distributed around the hemisphere, and microscopic beam-channels from each radiation source, all converging at a single central point. After several years of development work, the Proton Knife was ready to be replaced by Gamma Knife. At least in theory.

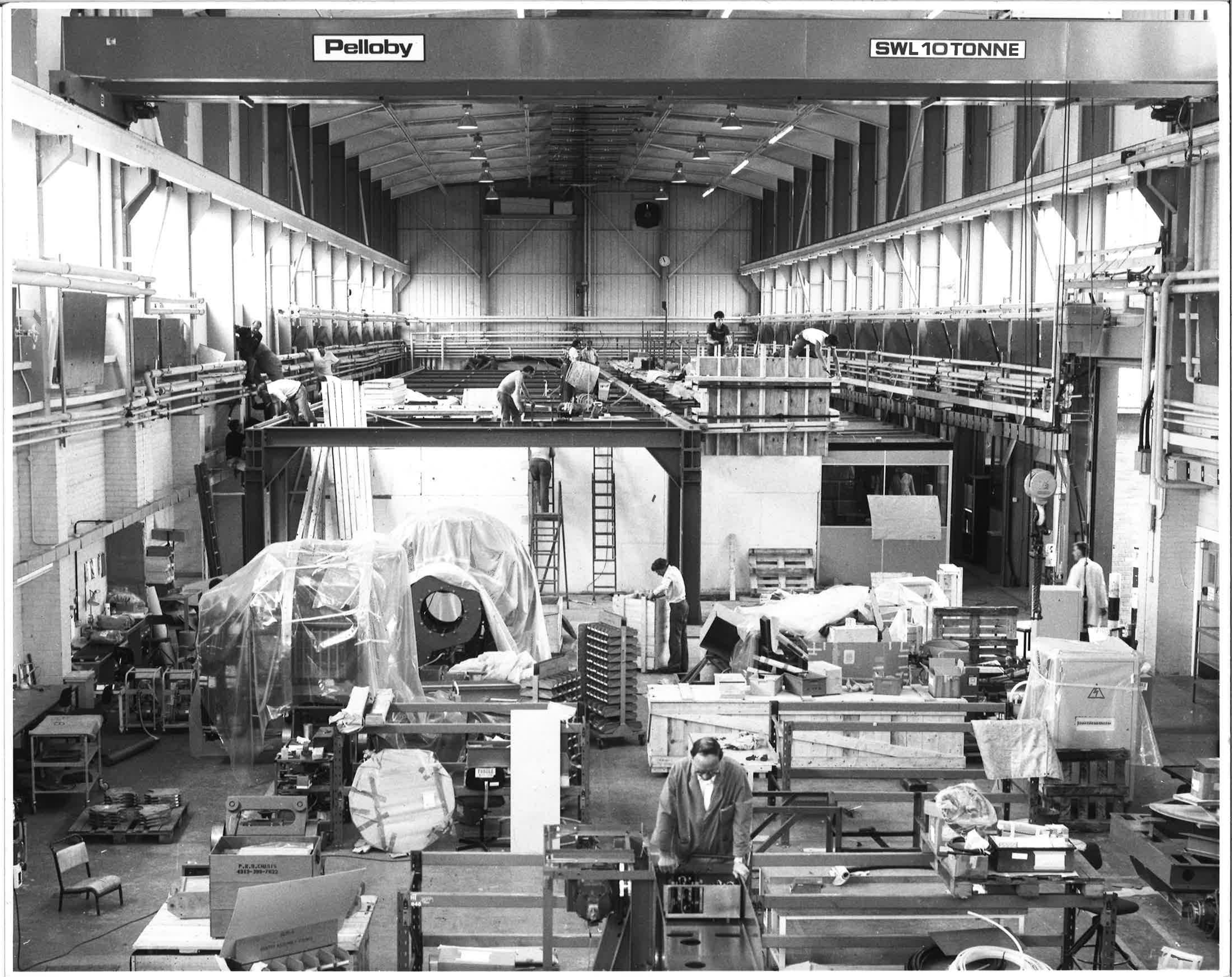

To convince the reluctant neurosurgical community, Leksell and Larsson clearly needed to construct a prototype of the machine. This was not a simple task—finding a workshop with the technical skill and equipment to carry out exacting work of this kind could have posed a problem if fortunate circumstances had not interfered. The Gamma Knife development work had been mainly funded by the Axel Johnson Research Foundation, connected to the large and diverse Johnson Industrial group. The Johnsons now suggested a surprising solution. Among the companies in the Johnson conglomerate was Motala Verkstad, among Sweden’s oldest industrial companies. Motala Verkstad had been founded in 1822 to provide equipment to the construction of the Göta kanal, a waterway connecting the East and West coasts of Sweden. Since its foundation, Motala Verkstad had been producing everything from ships, bridges and locomotives to airplane landing gear and kitchen sinks. They could probably build a Gamma Unit too.

What seemed at first an unlikely combination turned out to be a perfect match: the oldest mechanical workshop in Sweden happened to be just right for producing advanced and sophisticated equipment for radiation neurosurgery—a medical discipline that was as yet barely established. In fact, Motala Verkstad was exceptionally suited for the job—particularly the extreme precision drilling required to make the 180 radiation channels of the Gamma Unit’s helmet. One of the many products from Motala was ship propellers; to make the long cooling channels at the center of each propeller shaft took a precision similar to the one needed for Gamma Knife radiation channels. Motala Verkstad was commissioned to build the prototype and is still making Leksell Gamma Knife systems sold all over the world.

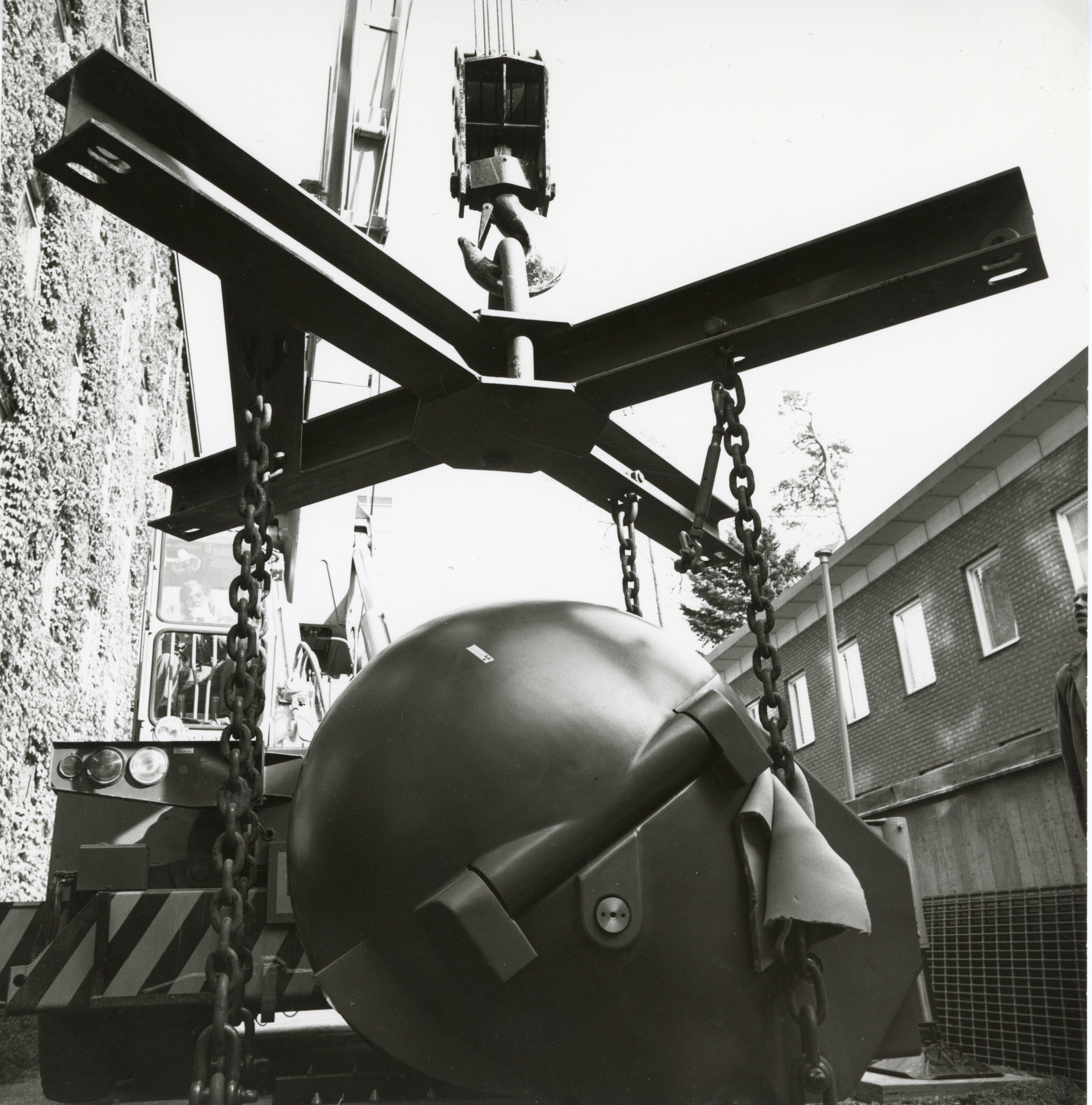

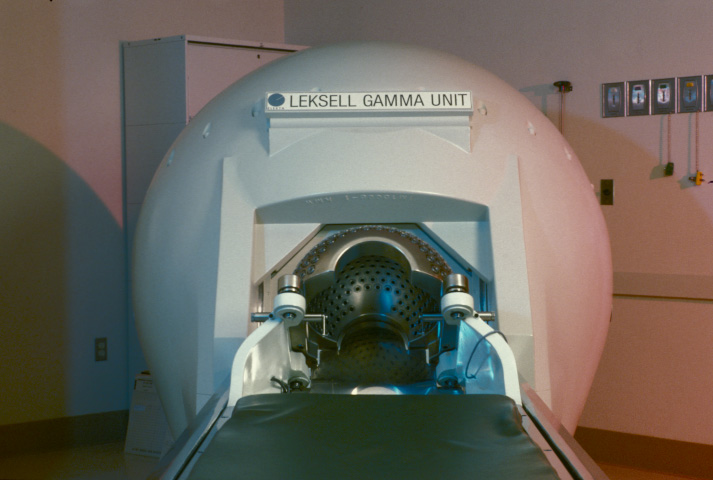

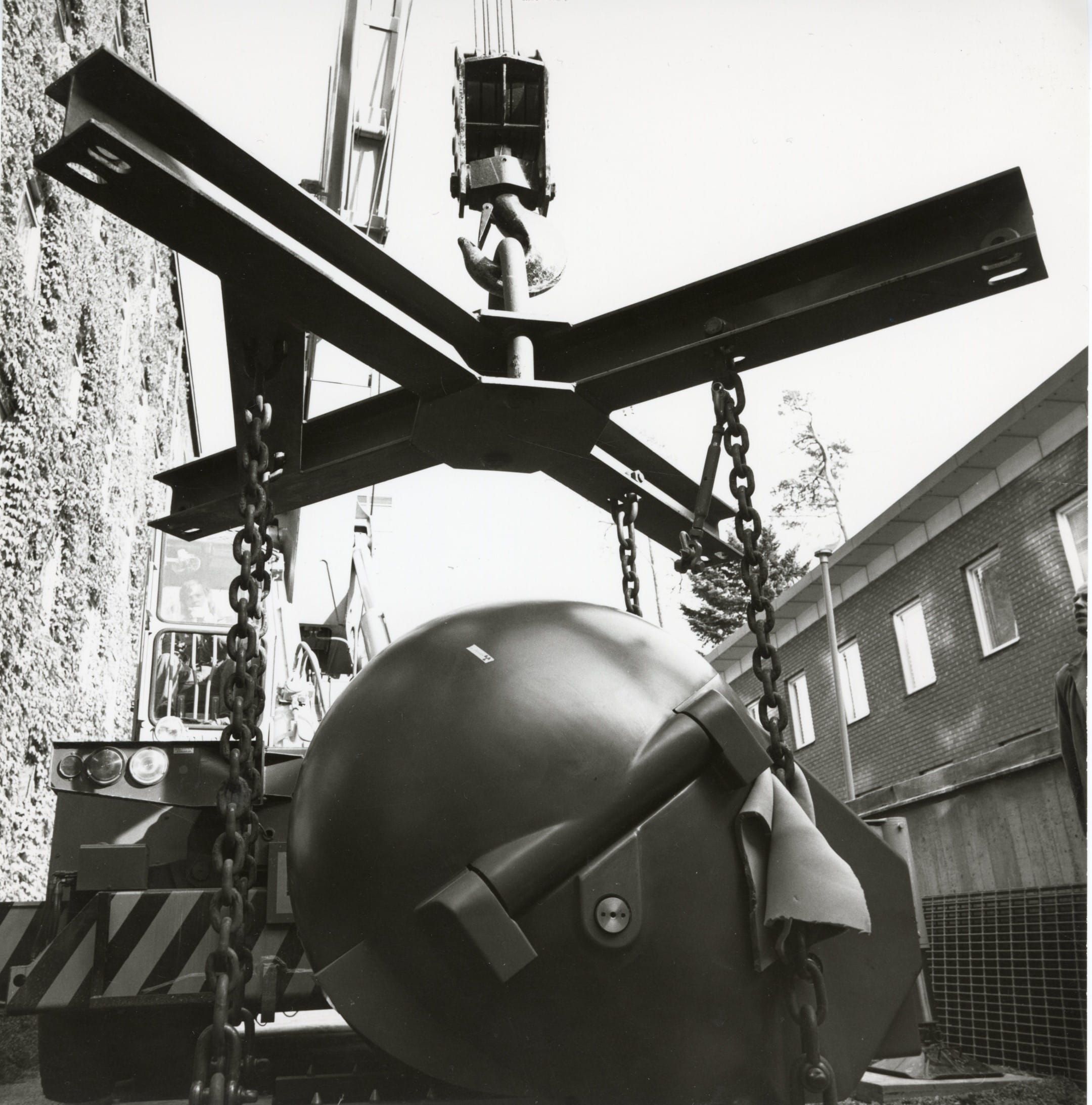

In 1967, the prototype Gamma Unit was completed. The mechanical engineer Hans Sundqvist at Motala Verkstad had played a vital role in solving the prototype’s mechanical problems. The Unit was popularly named “Kulan” (the Ball) because of its resemblance to an oversized football or motorcycle helmet. It was intended for the Sophiahemmet Hospital in Stockholm, but first it had to be loaded with radioactive material. Therefore, it was transported from Motala to the research nuclear reactor R2 in Studsvik, outside of Nyköping.

There it was loaded with Cobalt-60 sources—but only 178 instead of the intended 180. The workshop had failed to drill one of the radiation holes and another one had to be plugged because it was positioned outside of the reference area of the machine. Still, the Gamma Unit was ready for use. The Stockholm hospital, however, was not prepared to accommodate it yet. What was lacking was permission from the State Radiation Protection Institute (Statens strålskyddsinstitut) to handle radioactive Cobalt-60 for medical and research purposes at the hospital. This dilemma illustrates the radically new situation—hospitals were not ready or equipped to house radioactive substances or to handle them in their daily work, nor were regulations adjusted to these new practices.

In frustration, the team decided to perform a first operation on location at the nuclear reactor in Studsvik, rather than to lose more time. And so, on November 2, 1967, the time had come for the first Gamma Knife operation. The patient, suffering from a serious craniopharyngioma (a rare type of noncancerous, or benign brain tumor) was taken by ambulance from Stockholm to Studsvik, and Lars Leksell traveled in his own car, together with neurosurgeon Erik-Olof Backlund, head of the radiosurgical team. Incidentally, their car had a motor failure on the way to Studsvik, which nearly prevented the whole operation. Fortunately, the problem was solved, and the two surgeons were able to reach their destination, even if slightly delayed. Also, Börje Larsson from Uppsala and Hans Sundquist from Motala were present during the event.

One eyewitness of this historical event was Lars Leksell’s son Dan, then a 17-year-old student. He describes the experience as unreal: “Well what can I say, it was completely—wow … You didn’t see anything. The patient went into this ball, and then after an hour the patient came out, and was driven back to Stockholm. You had no idea what was going on in there. An operation but no blood. It felt very strange.”

“An operation but no blood. It felt very strange.”

Radiosurgery versus radiotherapy

Leksell’s gamma ray method was non-invasive and thus gentler approach than opening up a patient’s skull for open surgery. However, it was in many ways still a surgeon’s method; the radiation doses were distributed with great precision to very small areas, leaving behind only disc-shaped lesions in the brain, lesions that looked much like the lesions a scalpel would make.

The media called it “non-bloody brain surgery” and radiosurgery became a new clinical discipline. And although it could be used for several intracranial neurological indications in the head, its reputation soon centered on how it could treat brain cancer.

Radiosurgery differed greatly from radiotherapy, which was the traditional way of treating cancer. For one, conventional radiation treatment was administered by radiation therapists and not neurosurgeons. Further, the dose was delivered over several sessions, and not in a single session. And the radiation hit not just the malignant area but also struck healthy tissue outside of the target area.

Radiation treatment used linear particle accelerators, or linacs for short. A linac generated x-rays and high energy electrons that could be used on tumors. The method had a long tradition in the medical field, with principles established in the 1920s and then put to clinical use in the early 1950s. It had its clear downsides compared to Gamma Knife—the unnecessarily large treatment field and the need for multiple sessions—but had one obvious advantage: it could be used for the full body.

These usage differences came quite simply from how bodies work. Gamma Knife “cuts” with a high-intensive and very focused beam, and there is no room for error in hitting the target area. This works well with the brain, which is a relatively stable area in the body. A neurosurgeon can look at an MR image from a day before surgery and assume that the target area hadn’t moved. Fixing the patient’s head and using stereotactic equipment then further enables the precise positioning necessary for Gamma Knife.

But the rest of the body behaves differently than a brain. A lung moves with every breath and with it the tumor that might be in it. Or a prostate changes in size and position as the bladder fills. Anyone delivering radiation to such areas has to compensate for organ movement—which could occur at any time, including during treatment.

Conventional radiotherapy adjusted for this anatomical behavior by delivering broad spectrum treatment, split up over many sessions or “fractions,” knowing that healthy tissue inevitably would be affected. Spread out over time, this didn’t matter since healthy tissue recovered quicker between the sessions than diseased tissue. By contrast, Gamma Knife couldn’t touch healthy tissue without causing severe damage. Larry Leksell explained: “The typical example is the prostate. If it moves a centimeter, and you miss the target area with Gamma Knife, you will cut through intestinal walls and most likely cause complications.”

Going corporate

Lars Leksell was a dedicated surgeon and innovator, driven by a combination of curiosity and ethical commitment, in addition to an aesthetic will to find the simplest, and therefore most beautiful solution to clinical challenges.

But he was no entrepreneur.

When colleagues in the international neurosurgical community wanted to order one of the Leksell Stereotactic instruments, he used to direct them to the small fine-mechanical firm Stålex AB, which produced the instrument on commission, without marketing the product to any great extent. As for Gamma Knife, Leksell estimated that three to five units would be enough to cover the entire world’s future needs. History would prove him grossly underestimating his own invention.

Instead, the suggestion to build a company around Leksell’s inventions and patents came from his 20-year-old son Laurent, or Larry, who was finishing his first year as a business student at the Stockholm School of Economics. Lars Leksell had a registered a single-person firm named “Elekta Instrument, Lars Leksell,” but as Larry pointed out, an incorporated company would reduce the tax costs considerably and release revenue to be invested in new research. It could also make it easier to apply for research money from state-funded research agencies. The senior Leksell agreed to the idea, granted that he himself could focus on his research without being involved in business matters. The issue was settled.

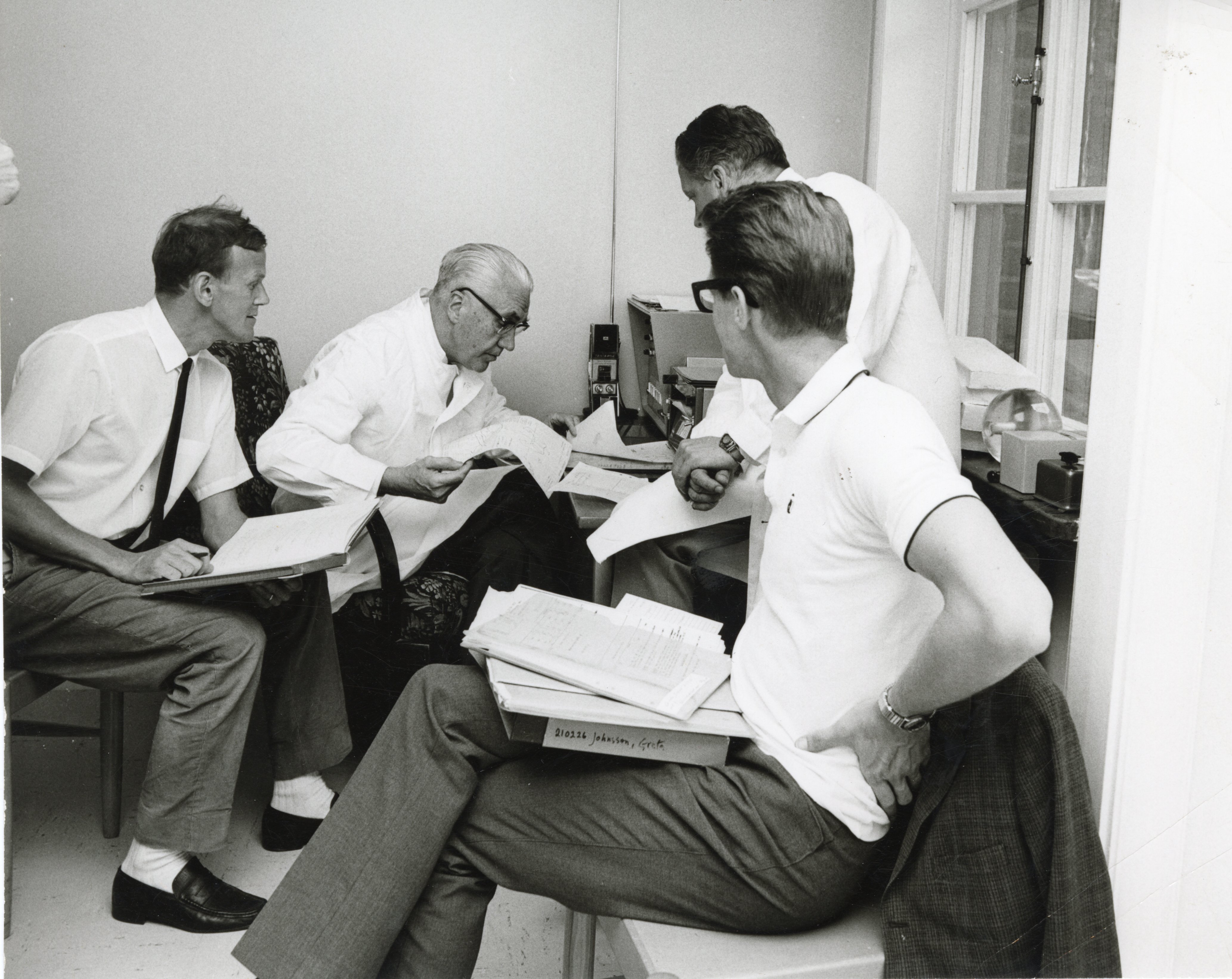

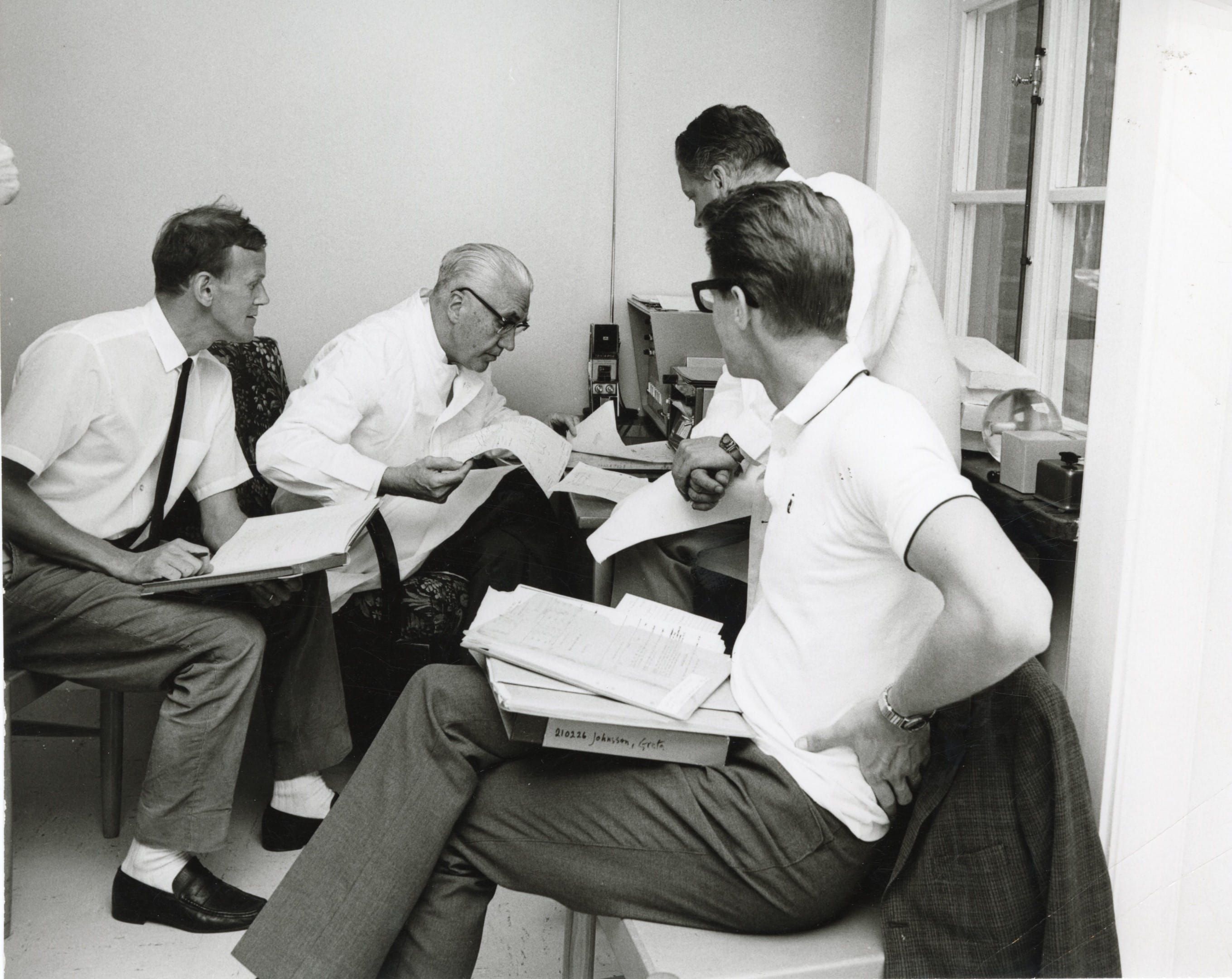

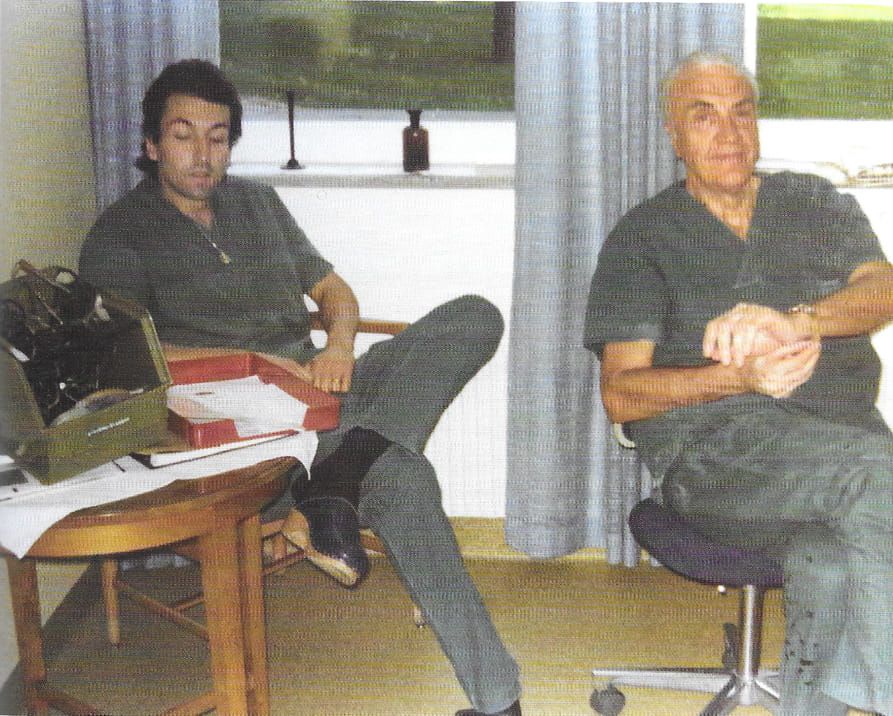

”Aktiebolaget Elekta Instruments, Lars Leksell” was registered on October 10, 1972 (from 1974 Aktiebolaget Elekta Instrument). The name Elekta – from the Greek word elektos, meaning chosen or elected – was kept from Lars’s previous company. Initially, the company was a family affair, with Larry Leksell as the CEO and his elder brother Dan, or Danny, who was finishing his studies to become a physician at the Karolinska Institutet, as Medical Advisor. Both brothers were unsalaried. Katarina Lilja, at the time married to Danny Leksell, was employed part-time to manage accounting, invoices and bills.

“With a logo designed by Larry’s schoolmate Kalle Olsson, Elekta was ready to do business.”

The company office was accommodated in one of the rooms of Lars Leksell’s apartment on Strandvägen in Stockholm. The first board consisted of Lars, Larry and Danny Leksell, and the company’s business lawyer, Björn Marklund. The share stock was divided equally between Lars Leksell’s five children. With a logo designed by Larry’s schoolmate Kalle Olsson, Elekta was ready to do business.

A second knife

At the time Elekta was founded, there was only one Gamma Knife unit in operation in the world. It was the same prototype that had been used to perform the first operation in Studsvik five years earlier. The unit had since been moved to the Sophiahemmet hospital, as originally planned, in 1968. Shortly thereafter, the second operation using the unit was performed on a patient with a benign pituitary tumor. Some 15 more operations followed that year.

However, the prototype unit at Sophiahemmet soon needed to be replaced, and the natural location for a new Gamma Knife would be the emerging radiosurgical unit at the Karolinska Hospital, Lars Leksell’s own research milieu. The investment was significant and gave rise to long-spun discussions about the benefits and limitations of the new treatment method. The hospital eventually found itself having two options. One option could be to build on the departments of radiotherapy and medical physics, which proposed investments in radiotherapy with linear accelerators, capable of treatment of cancer and other diseases in the whole body, but without the precision to single out specific injured tissue. Alternatively, the hospital could center around Leksell and the neurosurgical department, favoring the precision of Gamma Knife, a solution specifically developed for brain treatment.

Partly, this was a dividing line between oncologists and physicists on the one hand, and neurosurgeons on the other. Among the sceptics was, at least initially, Radiumhemmet’s director, Jerzy Einhorn, who was the intended host of the device. Leksell’s personal standpoint was clear: he had tried treatment with linear accelerators and found it unsatisfactory, while Gamma Knife, of course, was his own invention. And, as he put it: “The Gamma Knife is a surgeon’s tool.”

Finally, the hospital administration decided to support Leksell’s position, and in 1973 an order for the second Gamma Knife was placed at Motala Verkstad. Compared to the first unit, this one had several significant improvements. Among other things were three different, interchangeable, sizes of “helmets” with varying radiation diameter. It also had a different radiation target shape – the prototype had a narrow, disc-shaped target, the new machine had a spherical one. This made the device suited for more diverse uses, not least for tumor treatment. The machine was installed in the High-voltage Room of the Radiumhemmet in late 1974, the same year that Lars Leksell formally retired from his post at Karolinska Hospital.

A troublesome start

The world’s second Gamma Knife was now up and running, but even though this was a significant accomplishment, it did not bring profit to the Elekta business. Both of the two first units were partly financed by support from the Axel Johnson Foundation and other sources, and were not, strictly speaking, regular firm deals. In fact, the company turnover after two years was only 200,000 SEK, from selling patent rights for Lars Leksell’s instruments, like the Leksell Rongeur or the Stereotactic Instrument, produced by various actors.

To find a buyer for a third Gamma Knife was more challenging. The next customer would probably have to be an international one, as the Swedish market for Gamma Knife systems was saturated, at least for the time being. But the radiosurgical method was still contested and relatively unknown internationally, and each Gamma Unit represented an investment of between three and four million USD. This meant that each contract demanded patience and long-term trust building.

On top of this, the company assigned to produce the two first units, Motala Verkstad, had run into serious financial troubles due to the early 1970s crisis in the oil and shipbuilding industries. In a couple of years, Motala Verkstad had reduced its workforce from 4,000 to 300, and was no longer able to carry through a new Gamma Knife deal. A new subcontractor had to be found.

Ironically enough, the first bid to buy the production license went to a company that later became Elekta’s main competitor—the US’s Varian Medical Systems—which declined the offer. Instead, the choice fell on the Uppsala-based tech-company, Scanditronix, which specialized in nuclear innovation technology and particle accelerators. The firm, in turn, would sub-license the actual production to a Swiss subsidiary named Nucletec.

In the meantime, Lars Leksell—a very active retiree indeed—continued to improve his inventions. The mid-1970s saw the first digital three-dimensional x-ray visualization techniques, so called Computerized Tomography, or CT scanning. With more accurate images of the inside of the brain, this offered new possibilities for the Leksell Stereotactic System. By combining these two techniques, he thought, the precision in stereotactic neurosurgery should increase considerably. Leksell started experimenting, but this meant that the stereotactic frame had to be redesigned. The work would prove vital for the long-run development, but it was also very expensive, and the company was not able to cover the costs.

In 1979, Elekta was in acute need of working capital. Its owners, Lars Leksell’s children, had no ability to add new capital and the company was nearly bankrupt. To find a way out of the dilemma, Larry Leksell obtained a personal bank loan of 300,000 kronor and proposed to his siblings that he would take over the entire ownership. The family agreed and the company was saved, at least for the time being. Business, however, remained slow.

The early deals

In 1982, ten years after its foundation, Elekta appeared to have made very little progress as a company. It was still a part-time engagement for both Larry and Danny Leksell, with only one salaried employee. And Stockholm was still the only location for a Gamma Knife unit in the world. But under the surface, things had begun to move.

That year, Larry Leksell defended his doctoral thesis in economics at the Stockholm School of Economics: “Headquarter-subsidiary relationships in multinational corporations.” He also started a consulting bureau, Nordic Management AB, which successfully mapped Swedish firm ventures and strategies in the USA, on behalf of the Handelsbanken. The assignment was followed by others, and the company expanded quickly. This provided a solid income for Larry, and Nordic Management could even make a limited office space available for Elekta.

Another strategic ball was also set in motion. For decades, medical students and aspiring surgeons from different countries had spent time at Lars Leksell’s clinic in Stockholm, to work and study with the controversial, but charismatic and internationally, renowned professor. Several of these students were now influential neurosurgeons in their own right, often also heads of clinics in hospitals and research centers across the world. These people proved invaluable ambassadors for their mentor’s ideas. The first international Gamma Knife deals of Elekta were all connected to such individuals.

The first were two Argentinian neurosurgeons. Roberto Chescotta spent time as a student at Leksell’s clinic, and Hernan Bunge had been in contact with Leksell during his time as a student with Gösta Norlén at the Sahlgrenska Hospital in Gothenburg. In 1982, Chescotta and Bunge took initiative to install a Gamma Knife in the Clinica del Sol in Buenos Aires. Shortly thereafter, the British neurosurgeon David Forster, who had worked with Leksell at the Karolinska Hospital in the early 1970s, was granted permission to order another Gamma Knife for the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield.

The Buenos Aires unit was the first to be built by Scanditronix and its Swiss subsidiary company. Unfortunately, the cooperation took a bad turn from the start, with disputes over the licensing agreement and payments, but also over a long list of technical issues. When the Gamma Knife was installed in Buenos Aires in 1983, preliminary safety tests showed that the unit was not working properly.

A special team with Danny Leksell, the physicist Jürgen Arndt and engineer Hans Sundquist was sent to deal with the difficulties on site. New faults were detected, new trips were made, and faulty parts were continually returned to the manufacturer in Switzerland, until finally the unit was working properly. The process had been exceedingly troublesome and of course expensive—especially for the subcontractor Scanditronix.

Luckily, the installation in Sheffield went a bit more smoothly. But by then, Scanditronix had changed ownership and lost interest in further cooperation. No more Gamma Knife systems were ever constructed by Scanditronix. The relationship ended as it had begun, with disputes about compensation, licenses and rights to original designs.

However difficult, the first international orders had started the ball rolling, and Elekta was now turning its attention to the important US market. A sales office had been set up in Atlanta as early as 1982, under the leadership of Canadian John Rigby. But to land a deal for a Gamma Knife was an entirely different matter.

It was yet another old acquaintance of Lars Leksell who would serve as a door opener for Elekta in the US. L. Dade Lunsford, who had been a pupil to Leksell and Erik-Olof Backlund in Stockholm during 1979–81, now held a position as a neurosurgeon at the Presbyterian University Hospital in Pittsburgh. He persistently advocated the acquisition of a Gamma Knife to the hospital. His efforts would bear fruit during late 1986, when a contract was signed between the hospital and Elekta.

The Pittsburgh deal was undoubtedly Elekta’s most significant contract to that day, and still stands out as pivotal in the company’s entire history.

Sadly, Lars Leksell would not live to see it happen. At the age of 78, he died unexpectedly of a heart attack in January 1986, during a spa visit in Bad Ragaz in Switzerland.

These two events—the death of the company’s originator and the first successful Gamma Knife deal in the US—marked a watershed in the development of Elekta. At this point, the company could just as easily sell itself to another company, rather than keep developing on its own.

An important decision by Lars Leksell’s son Larry paved the way for the next phase in Elekta’s history.

Did you find it interesting?

Feel free to share it across social media!